Money laundering Zimbabwe-style

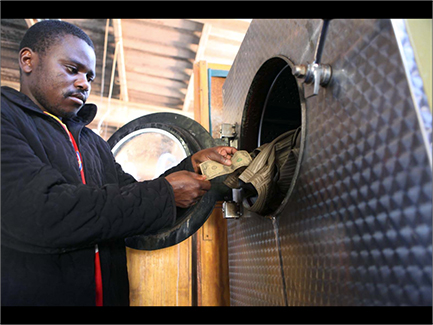

Harare – The washing machine cycle takes about 45 minutes _ and George Washington comes out much cleaner than before in Zimbabwe-style laundering of dirty money.

One US$ bill has been circulating hereabouts since 1999 when Lawrence H. Summers’ signature was put on it during his three-year tenure as Secretary of the U.S. Treasury. It is grimy, stained and almost black.

Low denomination U.S bank notes have come a long way across the African continent and change hands until they fall apart, having been hidden, smuggled in car tires and carried often in underwear and shoes through crime-ridden slums.

Storekeeper Jackie Dube hasn’t yet taken up advice of friends to start washing the often damp and stinking U.S. dollar takings receives for the garments and cheap Chinese consumer goods she sells in Harare.

“I’m a cash business and I don’t have the time. I need quick turnover, and I get rid of the worst of the notes as soon as I can in change,” she said.

Some bills are almost too smelly to handle and, said one Zimbabwe shopper confronted by a wad of disgusting notes, “I’m feeling tempted to carry rubber gloves in my purse or at least disinfectant wipes.”

Zimbabweans trading in the American currency since their own hyper-inflationary notes were abandoned in 2009 say washing their dirtiest cash works.

The U.S. notes do better in gentle hand washing in warm water.

At a laundry and dry cleaner in eastern Harare, a machine cycle does little harm either to the cotton-weave type of paper _ for security reasons, the U.S. Federal Reserve has never officially divulged exactly what the bills are made of _ though chemical “dry cleaning” is not recommended. It fades the color of the famed greenback.

Neither laundry cycle shreds the bills or damages the security features the first time around.

Laundry worker Alex Mupondi said a customer asked him to try machine-washing a selection of bills and the result impressed him.

According to the Fed, which destroys about 7,000 tons of worn out money every year, the average one dollar bill circulates in the United States for about 20 months, nowhere near its African life span of many, many years.

Across Africa’s troubled, struggling economies the American buck speaks louder than local currencies in shady black market deals and at informal bazaars and markets. It has been the unofficial currency of the shanty towns of the Congolese capital Kinshasa for decades.

Since Zimbabwe troops were deployed to fight alongside Congolese government forces in 1998 to defeat rebels there, Zimbabwean mining, trucking and trading businesses have flourished in the mineral-rich, corruption-plagued Congo, a longtime ally of Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe.

Those businesses and regional merchants eased initial shortages of U.S. money after Zimbabwe’s short lived coalition government declared it legal tender to eradicate world record inflation of billions of percent on the local Zimbabwe dollar.

Among Africa’s poor, small denomination U.S. bills _ $1, $2, $5 and $10 _ are the most sought after. Larger denominations coming in through banks and formal import and export trade are less soiled.

The Fed says in U.S. conditions the $10 and $20 bill last about two years and the $5 lasts an average 16 months, slightly less than the $1 there.

The $2 note, common though faded in Zimbabwe, is rarely seen in the United States.

Banks and most businesses in Zimbabwe won’t accept torn, Scotch-taped, scorched, defaced, exceptionally dirty or otherwise damaged U.S. notes, unless they can redeemed through the U.S. Treasury.

A torn $50 bill can be used for less than its face value in Zimbabwe’s impoverished townships. It and dirty George Washingtons from Jackie Dube’s corner store can remain in circulation at rural markets, bus parks and beer halls almost indefinitely _ or at least until they finally disintegrate.

-AS