Haiti, I always wondered why – and more now with the hand-wringing over history

Having been to Haiti in my professional meanderings a while ago, I have often wondered what made it such a fascinating place but such a scary one to spend time in.

Having been to Haiti in my professional meanderings a while ago, I have often wondered what made it such a fascinating place but such a scary one to spend time in.

Its colonial history is unique. A rebellion against the French colonisers brought independence 200 years ago. But nothing about Haiti is that straightforward.

The French sold the territory back to its people which the Haitians could never pay – the price demanded by France for this patch of a torrid Caribbean island inhabited by former slaves, according to Marlene Daut, writing recently in The Africa Report, was far more than any European country of the day would even consider laying out for any of their peculiar ventures. The French wanted 150 million francs in reparations for losing their colony and their properties, not the other way round. It bankrupted the place from day one.

At first, the Haitians were forced to borrow 30 million francs from French banks. Then the French reduced the total debt from 150 million to 60 million francs in 1838 in what was a cynically French “Traite D’Amitie” (Treaty of Friendship.)

As recently as 2015, then French President Francois Hollande conceded that France owed Haiti at least US$ 28 billion but it was a ‘moral debt’ not a binding one under international law.

Over the years Haiti plunged deeper and deeper into eternal poverty, worsened often by Caribbean hurricanes and the catastrophic earthquake in 2010 that killed 200,000 people. If anyone needs reparations for colonialism in the age of Black Lives Matter, it is Haiti, says Marlene Daut.

The colonial Oloffsen hotel, a once private home described as a 19th Century Gothic gingerbread mansion, the fictional Hotel Trianon in Grahame Greene’s 1966 novel The Comedians, largely survived the earthquake. I – and the the likes of Jaqueline Onassis and Mick Jagger – frequented it in other times. Greene stayed there writing The Comedians.

The colonial Oloffsen hotel, a once private home described as a 19th Century Gothic gingerbread mansion, the fictional Hotel Trianon in Grahame Greene’s 1966 novel The Comedians, largely survived the earthquake. I – and the the likes of Jaqueline Onassis and Mick Jagger – frequented it in other times. Greene stayed there writing The Comedians.

Herein also lies the strangeness of Haiti: a rum punch on the terrace at the Oloffsen amid the frightening chaos and deprivation of the capital, Port-au-Prince.

With the French gone, the ancient rites of voodoo went from strength to strength and prevail. Other colonial powers had prevention of witchcraft laws – here in Zimbabwe our n’angas , witchdoctors in the politically incorrect word, are bunny rabbits compared to the practitioners of the Afro-Caribbean ‘religion’ of voodoo. In Port-au-Prince I saw human bones nailed to the lintel of the doors where voodoo lords lived. An arm bone meant the occupier was low ranking, a skull outside the house meant he or she was all powerful. Animal sacrifices and a voodoo doll pricked with needles against enemies are the most common Western perceptions of the old ‘voudon’ culture.

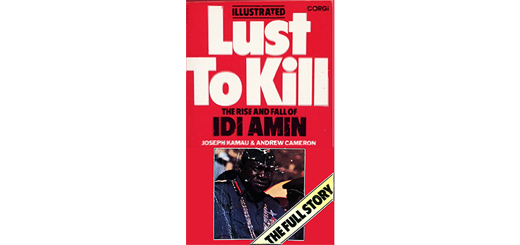

Haiti – love it our hate it. With its violent history – remember Baby Doc Duvalier and his vicious Tonton Macoute militias – there are many other disaffected places on the globe I’d rather revisit.