Chapter 1

TO THOSE WHO HAVE DIED

CHAPTER I

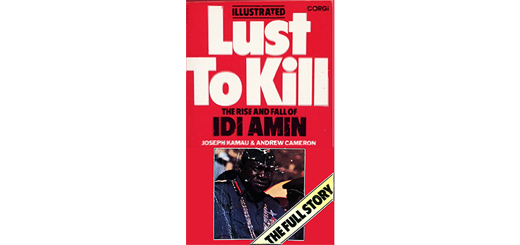

‘The time is now ripe for us very seriously to consider how best we can ensure that there is a permanent return to a sense of unity, freedom and liberty in Uganda.’ Major General Idi Amin Dada

Daybreak came abruptly – and with it, gunfire. Battle prepared troops lay in position around Parliament building. Swiftly, soldiers threw up road blocks on the approaches, shooting out the tyres of cars parked in nearly streets.

Overshadowing the crack of sporadic gunfire and the clatter of soldiers boots as they dispersed to key positions was the rumble of tanks, on the move before 3:00 a.m, churning up the city’s thin Tarmac.

The day: January 25, 1971. The place: Kampala, capital of Uganda. It was a moment in which yet again the history of Africa was changing – being written in violence and blood.

Down the road from Parliament, which was due to resume soon after President Milton Obote returned from the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference in Singapore, a crack Uganda squad, the Mbuya Hill Battalion, stormed the Voice of Uganda radio station.

An early morning announcer, sub-machine pistol pressing into his ribs, fumbled to put on martial music. Jeeps squealed to a halt at the main post office complex. Telephone and telex lines were disconnected.

Twenty two miles to the south, a military convoy rumbled towards Entebbe Airport. A mile or two ahead of it, a saloon car was carrying four Catholic priests. One of them, Father Guerts, of the Canadian Order of the White Fathers of Africa, was saying his farewells to his three brothers-in-Christ.

They were early. The Sabena flight which would carry Father Guerts to Europe en route to Canada had not yet arrived.

The friends relaxed in the airport lounge, talking over small, intimate matters.

Volleys of machine gun fire broke the calm, followed by the thump of artillery. A shell burst through the airport’s main entrance killing two of the priests instantly.

Outside, soldiers quickly laid barbed wire across the runway, encircled the airport buildings and kicked their way into the control tower.

Today Father Guerts would not be going back home to Canada.

An NCO ordered three of his men to drag the shrapnel-torn bodies of the two white priests down to the banks of Lake Victoria. Crocodiles would soon find floating corpses.

Foreign tourists bound for Murchison Falls stood against a wall with their hands up.

‘Go back to your hotels. Do not move until you are told’.

Overhead the sun was nearing its zenith. Along the road not far from Entebbe Airport, crowds of flies had begun to swarm. The doors of the Hippo Bar remained shuttered. The flies had found more corpses to feast upon.

Mortar fire punctuated the rattle of automatic weapons in Kampala. A Land Rover carried seven bodies away from Parliament precincts. The door of the President’s office inside had been broken down. After bursts of shooting an armoured car positioned itself in the compound at the residence of French Ambassador Albert Thabault. City residents who had set out for work were told by soldiers to go home.

British High Commissioner Richard Slater warned his nationals not to venture out.

Fifty miles to the east fighting flared between soldiers of the Uganda Army 3rd battalion at Jinja. The Victors moved on to seize the Owen Falls Hydro-Electric dam and, that secure, began marching towards Kampala. The 2nd battalion headed for the city too – from its Mbarara base 150 miles to the south-west.

Soldiers surrounded the ruins of Mengo Hill palace where Acholi and Langi troops loyal to President Milton Obote were camped. Other detachments cordoned off Nsamba police barracks and the police training college a mile from the centre of Kampala. In a radio studio at the Voice of Uganda, Warrant Officer Class 2 Sam Aswa ran his eyes down a roughly prepared announcement. Aswa’s voice faltered.

‘The Uganda Armed Forces have this day decided to take over power from Obote and hand it to our fellow soldier Major General Idi Amin Dada … and we hereby entrust him to lead this our beloved country of Uganda to peace and goodwill among all.’

The transmission faded momentarily. ‘We call upon everybody …. to continue with their work in the normal way. We warn all foreign governments not to interfere in Uganda’s internal affairs. Any such interference,’ Aswa stammered, ‘….will be crushed with great force … because … we are ready.’ The Warrant Officer read a list of 18 grievances within the Army. ‘Power is now handed over to Major General Idi Amin and you must await his statement which will come in due course. We have done this for God and our country.’

Aswa pushed his cap to the back of his head.

Idi Amin Dada had listened to the announcement with inordinate satisfaction. A Sherman tank stood in the driveway of his luxury mansion build on the crown of one of Kampala’s seven imposing hills. Amin placed machinegunners on the roof of the building and paratroopers indoors. He renamed his home in Prince Charles Drive The Command Post. Amin walked out onto the sun terrace overlooking the city. Bodyguards shuffled behind him, keeping their distance. This was his moment. He was on top, looking down – at last. He eased his 6 ft. 3 in. 230 lbs. frame into an armchair pulled onto the terrace. The afternoon was dry and crisp. He loosened his belt and leaned forward to ease the pistol that had squeezed into his hip. Sweat stains mottled his olive-green fatigues. A young officer reported that Amin’s instructions that a curfew would be imposed from 7:00 p.m. to 6:30 a.m. had been carried out.

But the curfew was not observed. Towards dusk crowds flooded into the Kampala streets. Baganda cheer-leaders whipped up choruses of anti-Obote slogans. Patrolling Army jeeps crawled through the throng. Soldiers smiled, people shook their hands, kissed them, hugged them.

‘Oyiieeh! Thanks to God. Hail our saviour, Idi Amin. We are behind Major General Amin.’

‘Obote Afude!’ (Obote is dead!)

Motorcades of private cars appeared: the cars were crammed, decorated with banana leaves and coloured paper, and towing tin cans. Passengers shouted happily. Small children tagged along, waving banana leaves. The soldiers at roadblocks were apologetic. Occasionally they loosed off shots into the air. An Army jeep drove through the campus at Makerere University, its crew firing rifle shots into the air too.

Rural people arriving in Kampala swelled the carnival – they came in busloads, car-loads, on bicycles and on foot. In the countryside around the city, they said, the homes of Obote supporters had been burned, their cattle had been taken.

Buildings burned in Kampala too. Acrid smoke hung over the city; the fires glowing in the evening twilight. The crowds tore down portraits of Obote, smashed them, jumped on them. They brought out crumpled pictures of the Kabaka of Buganda to tack up instead.

In a toilet in the recently built 12-storey Apollo Hotel named after Milton Obote, a medium built man in neat lounge suit was cowering. Basil Bataringaya, Obote’s Minister for Internal Affairs, had cause to be frightened. He hoped he would not be found. It was a forlorn wish. He was known to too many who had reason to hate him.

He did not have long to wait. A whisper here, a message there and soon a small group of soldiers was breaking down the door to drag him out and beat him until he was unconscious.

Nearby in the lounge Obote’s wife Mira sipped tea, watched over by eager-eyed soldiers, as she scribbled messages to family and friends saying she and the children – 6-year old Akeno, 4-year old Atoke and three-year-old Engena – were unharmed. As she wrote on hotel stationery, she tried to shut out the mounting noise from the street outside – the screams of abuse about the man she loved.

She had married Milton Obote as a young aspirant politician in Uganda’s colonial days. She had been by his side as he had steered Uganda first to Independence and then himself to the Presidency.

Today he was five thousand miles away in Singapore. Briefly the news had reached Obote. As his wife was under guard in the Apollo, he was swiftly packing, leaving his suite at the Singapore Hilton to board East African Airways flight EC 733 for Entebbe via Bombay.

Soon after the Super VC 10, one of three which were the flag carriers of East African unity, took off he reclined in his seat in the first class cabin and closed his eyes.

His 27 colleagues – aides, ministers and secretaries – watched him closely. Two hour later he went to the aircraft toilet, washed and returned to his seat to sleep once more. Few around him were able to relax. Nobody spoke. As passengers in the economy section behind ordered lunch and drinks, the sad, sombre Uganda party refused food – and nobody ordered drinks.

There was nothing to celebrate.

At Bombay, Indian soldiers surrounded the aircraft. Indian officials handed Obote a Press Trust of India report. Information was still sketchy. Another ninety minutes passed before Obote joined Captain David Powell in the cockpit to hear up-to-the-minute radio messages. He emerged with tears in his eyes.

‘It is a great shame,’ said an air hostess. ‘I cannot help but pity the situation.’

Foreign minister Sam Odoka walked down the aisle. ‘I really don’t know what to say. We don’t know much. We hope whatever happened prosperity and stability will continue. That is what we have all worked for. That is the President’s wish. It is a private hell for all of us not knowing what is happening.’

The aircraft touched down at Kenya’s Embakasi airport at Nairobi at exactly 7:10 East Africa time. A tight police cordon – supervised personally by Kenya Police Commissioner Bernard Hinga – surrounded the jet-liner and within minutes Milton Obote was being driven at speed towards Nairobi’s Panafric Hotel. Installed overnight in top-floor rooms Obote received news that he and his principal aides would face execution by the Uganda Army should they return home. Kenya vice president Daniel arap Moi visited the top-floor.

Downstairs police and security men refused to allow newsmen to enter the hotel, remained tight lipped when questioned. Later, after midnight, Obote’s delegation left their rooms and came downstairs to be driven by the same escort back to the airport.

Moi went too. He had strict instructions for the flight crew of the EAA Comet jet. Pilot Colin Skillett was ordered to take the Uganda party to Dar es Salaam.

But, asked Skillett, what if Tanzania refuses landing permission? ‘I don’t care,’ said Moi. ‘Take him anywhere – but do not bring him back to Kenya.’

With President Julius Nyerere visiting India on his way back from the Singapore Commonwealth summit meeting Obote’s East African Airways Comet was met by Tanzania’s second vice president Rashid Kawawa. Kawawa embraced a stooping, strained and gaunt Obote. The Ugandan wore a black suit and a blue shirt without a tie. The Ugandan flag fluttered from a masthead at Dar es Salaam airport and the Ugandan presidential standard flapped on the wing of the black Rolls Royce which took Obote to Nyerere’s state house. The contrast to Embakasi was pointed.

Amin was inevitably to fall seven years later in 1979:

A looted storeroom at Amin’s mansion. He printed hundreds of tee shirts depicting him as The Conquerer of the British Empire, taken from a photo of the occasion he forced four white businessmen to carry him in a sedan chair. One of the businessmen, car dealer Bob Scanlon, was murdered soon after the photo was taken.